Some time ago a colleague and friend asked me to write something on this subject. “Alas,” he wrote, “no one teaches the kids and they don’t even greet each other during competitions.”

Of course, this was an exaggeration because, luckily, there are still those who teach it and believe in its importance. And then, it should be remembered, the FIE International Regulations not only provides it, but severely sanction fencers who refuse to greet their opponent. How poor, however, would be the value of this act if we would agree to do it only if forced!

I don’t think this is the place to demonstrate the human and social value of greetings: recognition, respect, courtesy, culture and identity, connection with others, communication and sharing of feelings and emotions and so on and so forth. A social lubricant that contributes to our and others’ well-being.

No, here I’d like to focus on the value of the Salute in the specific context of fencing, of our sport. A sport that has ancient roots and enviable traditions. A sport that has everything to lose if it forgets the connection with its history and with what distinguishes us as fencers.

I fear that many will smile at the idea that fencing – a niche sport, by its numbers, and often considered at risk due to the arise of sports much easier to understand and practice – could somehow feel superior. Yet try asking around, or to newcomers, where they got the inspiration and desire to pick up a blade and engage in bloodless duels: the heroes of swashbuckling movies and novels, the ancient warriors, the sword as a symbol of justice and power, the knights without blemish and without fear, loyalty, the defense of the weakest, and… so on, if you want to name your favorites. Because, if you think a little bit about it, you will certainly have some too: perhaps Zorro, maybe D’Artagnan, Scaramouche, Captain Fracassa, Don Quixote…

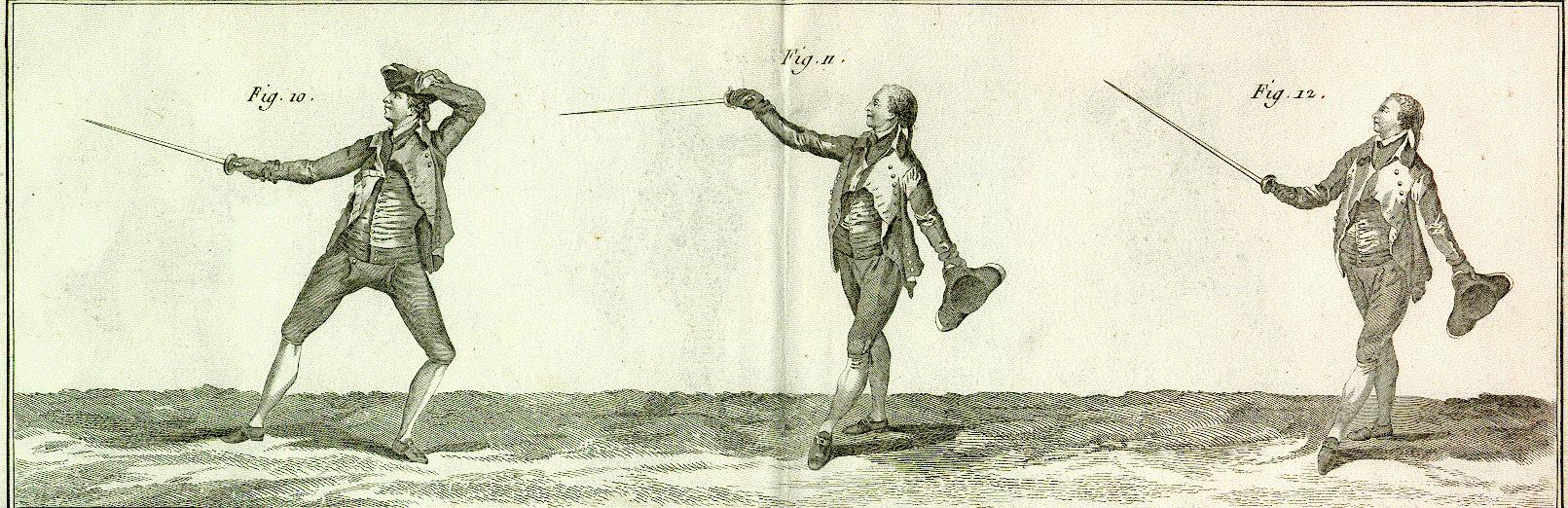

Perhaps the strongest archetype, in everyone’s imagination, is that of the armored warrior, of the knight, who meets his opponent and before facing him in a duel risking his life, introduces himself, greets him, lifts the sallet of the helmet, in a gesture that the soldiers of every country still make today, often ignoring its origin.

Now, however, thinking back to the colleague who proposed this topic to me, I would like to go back to the opportunities and benefits of teaching the Salute, in the relationship between the teacher and the students.

The lesson, individual or collective, should always begin with a Salute, which offers a splendid opportunity to explain the history and tradition of the gesture. I remember Renzo Nostini, President of the FIS (Federazione Italiana Scherma) for a long time, who told about the first lesson he received as a child: his teacher, who after having taught him the Salute, and having put the foil in his hand, said to him in a grave voice: “Now you are a gentleman and you must behave accordingly”

There are stories about the Salute act, perhaps not entirely founded, but which strike the imagination. For example (and this seems to me well-founded) that of the meaning, in the Italian Salute version, of bringing the armed hand up to the face, as if to kiss the cross formed by the quillon – the transversal bar typical of the Italian foil – with the ricasso, the part of the blade inside the guard, in the handle.

Another story, which I didn’t know, referred to me by my colleague, concerns the custom of placing a coin in the hand of the defeated enemy and squeezing it into a fist: from here, some say, the custom of shaking hands as a greeting would have arisen. I’m less convinced, but it’s another story that stimulates the imagination.

In addition to the stories, however, the execution of the Salute and the final handshake, offers the opportunity to correct inappropriate behaviors, making it a real educational tool.

The posture, the upright head, the gaze directed at the opponent and then at the other recipients of the Salute, a slight hint of a smile: all elements to point out to the student, explaining to him the meaning of what is being transmitted and also the psychologic importance of appearing confident and correct. The assault begins from there, and the impression the opponent gets from it, and vice versa, may carry a certain weight.

And then the final handshake, after the assault or the lesson: again, looking into the eyes, shaking the right way – how much information passes in that handshake and in that gaze! – with the body turned towards the other, as a sign of respect, whether the assault was won or lost and finally, not mumbled, but said with clarity and intention: thank you!

Finally, imagine the impression of the audience. A formal greeting, well executed, by two who have fought each other ferociously, but loyally, until a few seconds before, unites the winner and the loser in mutual respect and fixes in the mind of the beholder the image of fencing as we would like it to be.